US NAVY SEALS SEA)

Surprise!!! SEALs most valuable tool.

Although numb with shock, your body, seconds after hitting the icy ocean, moved into action with an instinct born of countless hours of training.

With a quick thrust of the legs, I plunged downward. Moving with the confidence of a man who knows exactly what he's doing, I quickly oriented himself and prepared for the evolution.

It was going to be a long night - a three-hour op in 42-degree water - no sense wasting time.

Even with the illuminated compass board, vision was limited to six inches in the inky black water. But, as a gentle squeeze on my arm reminded me, I was not alone. My dive-buddy was down there with me. Together we shared the danger as we made our way toward the night's target.

|

Just off the coast of St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, We entered the water from and inflatable boat in preparation for a string-line recovery operation. |

Just another day at the office for two members of a Navy SEAL team!

SEALs are unique in the special warfare community in that their capabilities include working on and under the water. This is often a dangerous mission; the ocean is unforgiving, especially at night. It is no place for shortcuts. There is only one way to operate : by the book and quick thinking.

It's a book whose text was drawn from the mistakes of others - sometimes fatal mistakes.

During the Grenada invasion, a new chapter was added to the book. Four team members drowned while attempting a rubber duck; insertion (jumping from a C-130, with a rubber boat, into the ocean). The lessons of that fateful night have been well learned and incorporated in the new SEAL SOPs. The same mistakes will not happen again.

Because of the acknowledged dangers of the job, SEALs go through what is considered by some to be the toughest training in the world. Whenever I'm really cold, wet, miserable and wishing I was anywhere but where I am, I think back and remember 'Hell Week.' Hey, I made it through that, This ain't shit! One of the reasons for such intense training is to weed out individuals who can't cut it - those who will quit when they get too cold, too wet or too tired.

| In full combat-swimmer garb, complete with bubble-free rebreather SCUBA gear and the MP-5 submachine gun, this SEAL emerges from the surf ready to strike! |

We work in small teams and depend on each other a lot, a whole lot. WE can't have anybody wimping out.

Trusting a teammate to do his part is important to the special camaraderie that develops within a team: We trust each other with our lives.

Whether performing hydrographic mapping, locking out of a submarine escape trunk or swimming up an enemy's beach for reconnaissance, team members literally place their lives in each others' hands. Working together is concept that is taught in basic training and reinforced over and over again throughout a SEAL's career. You learn you're not an individual, but a gear in a well-oiled machine,You are dependent on other guys and they are dependent on you.

|

Specially trained SEALs use SEAL Delivery Vehicles (SDV's) to cover vast distances underwater, undetected. |

Tied together by a six-foot line, dive-buddies work as a single unit to accomplish the job. If one part breaks down, the unit cannot function. We were attempting to plant limpet mines on a ship during a practice swim when my dive-buddy's diving rig flooded out. Diving with the LARV-5 Draeger, a front-mounted rebreathing rig, flooding meant a caustic cocktail for my partner. This is a particularly nasty mixture of fumes that results when the chemicals in the tank mix with water. At the very least, it causes an extremely bad taste and mild burns in the diver's mouth. In a worst-case scenario, a diver could die from the caustic fumes burning his lungs.

I was able to help my dive-buddy to the surface before any serious injury occurred. Luckily, we were near a pier when his rig flooded. We were able to surface under the pier and remain hidden.

To surface during a combat swim is the last thing divers are supposed to do, as it not only alerts lookouts to their presence, but also endangers other, undetected teams.

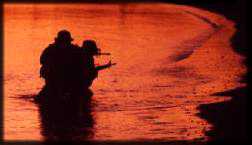

| Navy SEALs often use the cover of darkness to approach targets silently over and/or under the water. |  |

Surprise is a very important objective in our missions: To hit undetected and move out to the rendezvous point for extraction is our goal. You are usually OK if you can accomplish both objectives. If you lose one or the other, you're in trouble.

Although undetected and with the advantage of surprise still on his side, I could't finish the mission without my dive-buddy. We were so close to our target, I could have easily left my dive-buddy at the pier and finished the job myself. All I had to do was dive under and attach the Limpet to the ship. But that goes against everything we are taught. You never go anywhere without a buddy.

By the book.

As if danger from the enemy is not enough to contend with, there are the dangers of diving itself, such as bends or oxygen poisoning,current and positioning Not to mention other ocean inhabitants.

I remembered my dive-buddy meeting a great white shark on one dive. When the shark brushed past him, he jumped me. I'll never forget that moment. Two SEALs holding onto each other for dear life. All I could see were two giant eyes staring out from behind his mask. And I know that's all he saw of us.

Having encountered numerous sharks, one only six inches away, I decided sharks aren't that aggressive and their reputation is mostly hype.

Since most of the SEALs' missions take place in the middle of the night, we also must often contend with paralyzing cold and complete darkness. You can get pretty clausty (claustrophobic), pretty fast. Even with the insulating layer of water between the diver and his wet suit, it's a cold job. That coldness is only relieved momentarily when you answer calls from Mother Nature. You don't really have the time to concentrate on how miserable you are.

| SEALs spend many hours practicing every aspect of their dives and missions. |  |

Each partner has a job to do. For example, during a combat swim one man holds the compass board, which includes compass, watch and depth gauge, enabling the team to keep on course. His dive-buddy, holding onto his arm just below the triceps, serves as a lookout and counts kicks as a backup navigation aid. Using a code consisting of squeezes and pauses, the buddies can communicate underwater.

To be able to work well as a team requires a lot of practice. That's why each time a new dive-buddy is assigned, the partners get together and swim a hundred yards over and over again, until they know exactly how many kicks it takes them to cover the distance and how long it will take. Somewhere between two minutes and 50 seconds and three minutes and 10 seconds is the standard.

Before the team leaves on a mission, their underwater route is carefully planned - right down to the number of kicks it will take to reach their target. This is especially helpful as the team nears a large metal object such as a ship, which renders your compass useless. By knowing how much time and how many kicks it takes to cover designated distance, you can calculate exactly where you are.

They say familiarity breeds contempt. Not for us. The more we practice the better off we are.